Black Valley Clayton (BVC) – the youngest Clayton found so far -

A.

Acknowledgments & abstract (in

separate file)

B.

Expedition to The Sudan (in

separate file)

- A solution to the Clayton

ring problem (continued)

-

C. Discovery

of the Kufra Trail (in

separate file)

D. Discovery of the “Lost Ochre Quarries

of Kings Cheops and Djedefre” (in

separate file)

E. Discovery of late Neolithic rock art –

roots of early hieroglyphic writing (in separate file)

F. Black

Valley Clayton (BVC) – the youngest Clayton found so far

1. BVC

as a ceramic device belonging to a Muhattah on the Darb Wadai

2. BVC used by local pastoral nomads

3. Conclusions

F. Black Valley Clayton (BVC) – the youngest Clayton found so far

BVC was detected in the early morning of 10/27/2005 when tracing the Darb Wadai (DW – see Results of Winter 2005/6 – Expeditions - A Solution to the Clayton ring Problem). The item exhibits a notch combined with a beaded (roll shaped) rim. Because of its peculiar composition (for analytical details see Bourriau, J. D.; Nicholson, P. T. Rose, P. J.: Pottery. in Nicholson, P. T.; Shaw, I. (ed): Ancient Egyptian Materials and Technology. Cambridge 2000, pp.128-135) , which differs remarkably from known Claytons, it was clear to me from the beginning that this ceramic device was an exceptional piece of pottery.However, a German ceramics expert to whom I presented photographs of BVC last summer, was sceptical about my interpretation that the item had been produced on a potter’s wheel. In addition, Kuper´s team had, in the past, supposedly, been led to other Claytons which also exhibit a roll shaped rim. I was told that these were handmade, their dates of origin being considered to fall, as all others so far, into the transitional period between the pre-dynastic and early dynastic (approx. 3,100 cal BC, see Riemer, H.; Kuper, R.: “Clayton rings”: enigmatic ancient pottery in the Eastern Sahara. Sahara 12/2000, p. 96). This information was reason enough to revisit the site.

When heading for the location last winter and long before getting there, we crossed over three pairs of fresh 4WD tracks several times. The tire marks, zigzagging the otherwise virgin country, suggested that some individuals had been deliberately searching for Black Valley. When we finally arrived at the lowland, we ran into the same tracks just 5 metres off the site. All but two BVC-sherds were gone. As a memory of “good times” Black Valley and the very particular Clayton (pictures 1+2) found in it, are presented here again. (for more details concerning the item see Results of winter 2005/6 – expeditions)

pictures 1+ 2: Black valley; sherds of BVC

Similar looting took place at a pot sherd site in the eastern part of Ard Chalil, (marked on my map as “Scherbe + 2 Stk an Pyramide – pot sherd + two stone circles at pyramid hill”, see picture 65: expedition map of winter 2003/4, published in Results of winter 2005/6 – expeditions, Chapter E), which was approached by a single 4WD, and also at a site a few kilometres north of Muhattah Arba´a Mafariq (marked as “Clayton + Scherben - potsherds” on the same map), where all the 6th dynasty artefacts (some were lying in the hillock’s lee, while others had been deposited in a crevice about 3 metres above the ground) as well as a Clayton are gone. (the site was approached by two 4WD´s) As the same pair of tire marks were also found zigzagging the area between the junction of the Kufra Trail (see chapter C of this year’s report published in a separate document) and the TAB and Mery, there is, in this case, a slight chance that the above mentioned items were picked up by Kuper´s team.)

Anyway, in an attempt to protect such sites in the future, I shall refrain from publishing any more detailed maps and area views of archaeological locations. This will make it more difficult to identify and to approach the artefacts presented in my articles.

Having inspected the BVC sherd once again (in the helpful presence of another pair of eyes), I have to admit an error. This Clayton is indeed hand made. In Oct. 2005, during my first exited viewing, I was probably misled by BVC´s roll shaped rim which suggested a production of the item on a potter’s wheel. Even the picture 3 (taken on 10/27/2005) reveals an undulating surface on the two sherds to the right. These irregularities are caused by hand forming.

picture 3:

BVC sherds seen in Oct. 2005 revealing undulating surface above the roll

shaped rim

Concerning the question of the age of BVC, strong doubts remain, because the composition of its pottery (type of clay, filler etc.) differs much from that of a common Clayton. From the first moment I saw the item, I had anticipated that it would not fit into the time frame currently stipulated by Kuper.

BVC was detected adjacent to the Darb Wadai. On this road (a new and important discovery) which I traced up to Latitude 24 degrees 10´, two Islamic period water dumps (Ahmad ibn Tulun I + II) were found, one by Giancarlo Negro et al. and the other one by Tarek El-Mahdy. Contrary to G. Negro’s et al. estimates of a 4th dynasty provenance (see Negro, G,; De Michele, V,; Piacenza, B.: The lost ochre quarries of king Cheops and Djedefre in the Great Sand Sea (Western Desert of Egypt). Sahara 16/2005, p. 125) I had dated the road and the pottery to the early Islamic period (Later, I learned that a TL-date of 1100 +/- 20%, equivalent to 880-1320 AD, had been obtained from one of the dump’s potsherds, which pretty much corresponded with my estimate.). Since the BVC was found almost on the Darb Wadai itself and as the only other finds on this road were from the early Islamic period, I had assumed that BVC belongs to the same era. (see Results of winter 2005/6 – expeditions, chapter B.4.g) This was all I could do, as I am constantly lacking funds for conducting more precise inquiries of my own.

Later (in July of 2007), to my total surprise, I was notified that a fragment of the two BVC sherds, which had escaped the looting, yielded a TL-date of no less than 2,200 +/- 20% years. This is an amazing date; the youngest ever obtained for a Clayton! It proves that the desert to the south-southwest of Dakhla oasis was not completely void of human activity - even around 200 BC.

The site where BVC was discovered is two days distant (by donkey) from Dakhla. Concerning the site’s context there are three options:

- BVC was used by travellers on the Darb Wadai.

- The surroundings of BVC were temporary seasonal grazing grounds utilized by pastoral nomads of Dakhla oasis.

- BVC was a device put to work in a Clayton Camp.

The first two options will be discussed here, while the third one has to be put aside until Black Valley and the majority of its artefacts are better known.

1. BVC as a ceramic device belonging to a Muhattah on the Darb Wadai

Camels were introduced into Egypt in approximately 500 BC but the widespread use of donkeys had continued. So, although an individual in 200 BC could have travelled along the Darb Wadai by camel, this would have been most improbable as the value of such an animal at that time, would have been priceless. Therefore, it seems more likely that such a journey was performed with the help of donkeys, as it would have been out of the question for common people to afford the humped creature in Ptolemaic times. For comparison, most of those dwelling in Farafra oasis during the 1930s could not afford the price of a camel either (see my “Letzter Beduine”, pp. 307, 308) On such donkey expeditions to the south-southwest BVC had been used as a Handal pip roaster. (see Results of winter 2005/6-expeditions, chapter B.4 – A solution to the Clayton ring problem + this year’s report, chapter B. 2)

For convenience I shall make full use of my writings in the Results of winter 2005/6 – expeditions, where the climatic implications of my findings have been discussed at length.

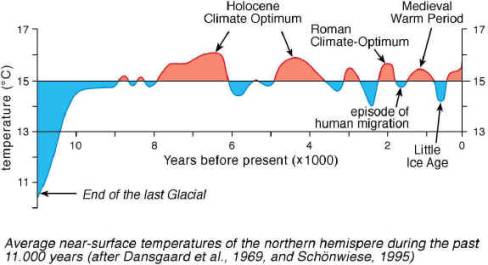

Picture 4 reveals that, at least from the perspective of the known palaeo-temperature variations, such a journey could have been possible.

picture 4: temperature changes during the Holocene (see Schönwiese, Chr.-D.: Klima im Wandel, Tatsachen, Irrtümer, Risiken. Deutsche Verlagsanstalt 1992; cited from: http://www.gfz-potsdam.de/pb3/pg33/kihzhome/kihz01/fig2_en.html

Temperature changes during the Holocene reveal that a.) the period, to which the TL-date of BVC belongs i.e., about 200 BC, is characterized by an upward-trend in global warming which, by then, had already transitioned into the onset of the “Roman Climate-Optimum”. b.) A similar upward trend has been noticed for the period of approximately 3,100 BC (see Results of winter 2005/6 – expeditions, chapter B.4.g). This is the epoch of transition from the pre-dynastic to the early dynastic era, the time to which three C14-dates, derived so far from Clayton sites have been assigned. (see Riemer, H.: News about the Clayton rings; long distance desert travellers during Egypt’s Predynastic. in: Hendrickx, S.; Friedman, R. F.; Cialowicz, K. M.; Chlodnicki, M.(ed). Egypt at its origins. Orientalia Lovaniensia Analecta 138, Leuven, Paris, Dudley 2004, pp. 976-978) c.) A comparable development took place in the period between 880 and 1,320 AD. To the early part of this period, circa 880 AD, (falling into the reign of the Egyptian ruler Ahmad ibn Tulun (868-884)) the pottery dumps on the Darb Wadai may be assigned (upward-trend of the Medieval Warm Period, the latter lasting from the 9th to the 14th century AD; see Results of winter 2005/6 – expeditions, chapter B.4.g).

It is surprising to note that in all three cases the age of the (,so far, dated) Claytons as well as that of the other pottery, matches with upward trends in global warming. Such evidence cannot be accidental. In Results of winter 2005/6 – expeditions, chapter B.4.g., I have ascribed the occurrence of Claytons (belonging to the pre-dynastic up to the early dynastic era) to a “last endeavour” to cling to a dying desert. This, certainly, can also be said for the BVC as well as for the DW-pottery. (According to Arab sources the Darb Wadai had been closed by the Egyptian ruler Ahmad ibn Tulun (868-884). “He did this because the route became very dangerous, as many caravans had been lost when covered by sandstorms or attacked by brigands.” (Al Istakhri, Kitab al-masalik wa´l-mamalik, cited from Levtzion, N.: Ibn-Hawqal, the Cheque, and Awadaghost. Journal of African History. IX,2 (1968) p. 232))

In 217 BC Hannibal crossed the alps with elephants. The diminished size of the alpine glaciers facilitated the march. What, precisely, does that mean for BVC, DW and the Western Desert of Egypt? As different “…regions have different sensitivity to global temperature variations.. one can reasonably argue that a true global average reconstruction requires scaling the different records to match local sensitivity.” (http://de.wikepedia.org/wiki/Bild:Holocene Temperature Variations.png. p. 5) However, so far, no such attempt has been made due to a lack of sufficient local data. Concerning the Libyan Desert and the above mentioned periods, it is also not clear, how temperature variations are linked with changes in precipitation. All that is known is that both do not necessarily correlate.

The archaeological evidence (Claytons and water dumps on the Darb Wadai as well as on the TAB + KT; see chapter C of this year’s report) would imply more movements across the desert during the Cold Phases preceding the abovementioned upward-trends in global warming. For the period of approximately 3,100 BC, as well as during the reign of the Egyptian ruler Ahmad ibn Tulun (868-884 AD) this is certainly true. If Ibn Tulun residing in far away Cairo, was induced to prevent passage on the Darb Wadai, the traffic on it, in the centuries before the closure (for instance in the era of the European Völkerwanderung) must have been remarkable as colder climate, most certainly, facilitated travel. Now, similar conclusions are being evoked by the TL-dating of BVC. This ceramic device, together with the Greek inscriptions, which I discovered at Muhattah Amur (a station on the TAB), and the Ptolemaic period pot sherds, which I came across south of Dakhla, are all indicative of travel during the Cold Phase prior to the Roman Climate-Optimum. Whether or not these movements were long distance ventures performed by donkey caravan still has to be investigated.

Referring to the era of the Old Kingdom, Riemer et al. have assigned manufacture and use of Claytons to an enigmatic, highly mobile population, which crossed the desert in small units by donkey. The authors believe that these travelling groups were in contact with a local Sheikh Muftah civilization (for instance in Dakhla oasis) as well as with that of pharaonic Egypt. (Riemer; H.; Förster, F.; Hendrickx, S.; Nussbaum, S.; Eichorn, B.; Pöllrath, N.; Schönfeld, P.; Wagner, G.: Zwei pharaonische Wüstenstationen südwestlich von Dakhla. MDAIK 61, 2005, pp. 346,347) In the light of BVC´s age determination such designation has to be modified. The Sheikh Muftah were dispossessed or exterminated during the First Intermediate Period (approx. 2,170 – 2,020 BC; ibidem). Their appearance and that of their counterpart (the “highly mobile population”) in the material culture of a desert environment 1,800 years after the extinction of the former is, by all means, out of the question.

On the limestone plateau north of Dakhla I found two badly eroded Claytons which also exhibit a roll shaped rim. (pictures 5 - 7) The “lids”, eleven in number, consist of re-utilised sherds from wheel-made pottery. The artefacts were left behind along an old trail which has been frequented right up until the beginning of the 20th century. Barring future dating that might prove otherwise, it may be assumed with some certainty that these Claytons also fall out of the time frame currently predefined by Kuper.

picture 5:

exp. 2001/2, Clayton “lids” picture 6: exp. 2001/2,

1st Clayton ring

picture 7:

exp. 2001/2, 2nd Clayton ring

2. BVC used by local pastoral nomads

As in the case of “Cheese-cover Hill” at El-Kharafish, on the limestone plateau north of Dakhla, a noteworthy discovery which I made in March 1989 (In winter 2000/2001, I had given the location to H. Riemer for archaeological investigation but soon after, Riemer, a man from Kuper´s team, impolitely suppressed my name and subsequently created the impression of having made the find himself. See Results of Winter 2005/6 – Expeditions, Postscript of 9/4/2006, chapter E. “Note concerning the treatment of a discovery made in March 1989”), the BVC site conveys the notion of a Clayton Camp or, at least, of a seasonal camp. There is rock art and quite a sizable, low semi-circular stone-construction (“windscreen”, erected against northern winds) in the middle of the Wadi. (see Results of winter 2005/6 – expeditions, picture 12). Also there is playa, there had been vegetation, there are stone implements and –flakes, and there is a ceramic device which had been used to roast Handal pips for human consumption. (for details see Results of winter 2005/6-expeditions, chapter B.4 – A solution to the Clayton ring problem + this year’s report, chapter B. 2)

Apart from the windscreen, the location where BVC was found is open towards the prevailing northern wind, which, most certainly, was welcomed. The site also provides some shade. Such an orientation indicates that the individuals who used BVC, were not concerned with the winter cold. They probably dwelt in Black Wadi during the summer time and would have enjoyed and benefited from monsoonal rain and its results.

Why would somebody dwelling in Dakhla oasis move to such a lonely place with his animals (goats, sheep, donkeys)? Is it because of the common conception that pastures that are farest away, are always the greenest? Ethnological evidence obtained from Air nomads illustrates that shepherds rarely run after mirages (Fata Morganae), and that their work (more than any other occupation) is linked to the empty wastelands proper. Even more: their work is perceived to take place in the wilderness only. “A good shepherd is one who seeks solitude.” (Spittler, G.: Hirtenarbeit. Die Welt der Kamelhirten und Ziegenhirtinnen von Timia. Köln, 1998, p.196)

Therefore, could shepherds have relied on rain water for their daily needs in areas, where permanent ground water was lacking? What was the weather really like around 200 BC? Although archaeologists have obtained hundreds of radiocarbon dates from the Western Desert, they have to admit, that “…climatic developments after 5,000 BC are not yet understood in detail due to the scarcity of climatic archives in the desert.” (Riemer, H., op. cit. p. 986)

In order to live in the Black Wadi wilderness for extended periods, it would have sufficed to load a donkey with a couple of goatskins as well as a bag of food and to take off from the last Dakhlanian well. Men and beasts could have obtained water from pools and ponds after rain, or they could have dug for it in playa sediments. For months, they would have lived on milk and cheese only. (see Spittler, G: op. cit., pp. 161, 261 + my observations in The Sudan; chapter B. of this year’s report published in a separate document) In addition, they would roast colocynth (Handal) pips as attested by the existence of BVC. To get rid of residual bitterness and to improve digestibility they would have added milk to their meal. (see Spittler, G.: Handeln in einer Hungerkrise. Tuaregnomaden und die große Dürre von 1984. Opladen 1989, p.168) Spittler conveys that the Air nomads always refer to milk, when reflecting on the importance of wild plants as famine food. (ibid, p. 170) Flocks of goats and sheep would graze in Black Wadi and its surroundings, partly feeding on green Handal that quenched the beast’s thirst. Such a self sufficient life could have lasted until the next rainy season which, no more than six months later, could have been a modest winter precipitation. (Please note that a mingling “…of two climate regimes, the winter rains from the north and west and the summer monsoonal rains from the south…” has been suggested for the Holocene humid phase (Kindermann, K.; Bubenzer, O.: Djara – humans and their environment on the Egyptian limestone plateau around 8,000 years ago. in Bubenzer, O., Bolten, A., Darius, F. (eds.), Atlas of cultural and environmental change in arid Africa. Cologne 2007, p. 26; for a discussion of the climate changes in respect to Biar Jaqub situated at about the same latitude as Black Valley see chapter D. of this year’s report)) and thereafter. (see Darius, F.; Nussbaum, S.: In search of the bloom – plants as witnesses to the humid past. in Bubenzer, O,; Bolten, A.; Darius, F. (eds), op. cit., p. 80)

3. Conclusions

The discovery of BVC in an area south of Dakhla oasis has thrown new light on an arid region which, according to the prevailing models, shows a distinct lack of moisture and water since the end of the Neolithic wet phase. However, the mere existence of BVC embedded into a cluster of artefacts substantiates the idea that life in the wilderness south of Dakhla, even in 200 BC, (or the crossing of this wilderness in order to reach far away destinations) was possible.

2,800 years after the period to which Claytons have been dated (around 3,000 BC), these ceramic devices were still being used for roasting colocynth pips. Although knowledge about the composition of the pottery (understood to include the composition of fillers and slips as well as the clay) had vanished, the memory of its form had endured.

I do not intend to suggest the continued utilization of Claytons throughout the period of circa 3,100 to 200 BC, based on this single unusual find with its “out of the ordinary” age determination.

What BVC and its surroundings do reveal instead, is that